Vitamin A and Measles: it doesn't replace the vaccine

Adequate levels of vitamin A, just as any micronutrient, are important for good health. However, deficiency in the US is rare and benefit of its use in measles therein is unclear.

In a recent op-ed about the current measles outbreaks in the US Southwest (mainly Gaines county in Texas), Robert F. Kennedy Jr. exceeded my expectations in noting the importance of MMR vaccination- but then he takes a left turn and says:

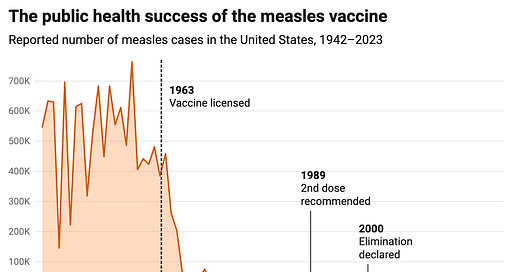

Tens of thousands died with, or of, measles annually in 19th Century America. By 1960 -- before the vaccine’s introduction -- improvements in sanitation and nutrition had eliminated 98% of measles deaths. Good nutrition remains a best defense against most chronic and infectious illnesses. Vitamins A, C, and D, and foods rich in vitamins B12, C, and E should be part of a balanced diet.

There’s more in the piece that merits dissection, but in the interest of maintaining a focused scope, I will concentrate on vitamin A here.

While the basic message that adequate levels of micronutrients are critical for health maintenance is true, the effect of nutrition is a distant second from the effects of vaccination against measles.

Here’s what you should know:

Vitamin A does appear to have a clear benefit in reducing mortality from measles in regions where there is significant vitamin A deficiency and particularly for children under 2. It is not clear whether it helps when a person is not vitamin A deficient, and vitamin A deficiency in the US and other higher income countries is rare.

While vitamin A can help to prevent mortality from measles, it is not shown to prevent other poor outcomes from measles beyond death (such as hearing loss, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, etc.). Only measles vaccines can do this.

Though there is some evidence that vitamin A can reduce the spread of measles, the effect is much smaller than that seen with measles vaccination and confounders on those data raise questions about how real this effect is.

We have previously had outbreaks of measles where despite the deployment of vitamin A per WHO recommendations, significant numbers of people died, such as in Samoa.

Vitamin A levels in blood are known to drop in response to infection and inflammation- this may not reflect true vitamin A deficiency because liver vitamin A reserves may still be plentiful.

Vitamin A supplementation should be done carefully with attention to the recommended daily allowances of retinol activity equivalents (RAEs); toxicity can be serious and children are at higher risk of developing toxicity.

Do not ever delay seeking care for measles (or any other disease) on the basis that you have offered supplemental vitamin A.

Supplement labeling information in the US should not be regarded as trustworthy. Inaccurate labeling tends to be the rule, rather than the exception. Dietary sources of vitamin A generally represent a safer route to ensuring sufficiency.

The focus on nutrition as being key to protection from infectious diseases misses the point that infectious diseases themselves can directly cause malnutrition- including measles.

For the details on vitamin A and measles, you’ll have to see the rest of the post.

Vitamin A

In lower- and middle-income countries (but not in the US), vitamin A deficiency is a major public health problem, particularly in children. Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) has multiple manifestations, but the most prominent are its effects on vision and immunological function. In the retina, vitamin A, in the form of retinaldehyde (aka retinal) is absolutely essential to the perception of light (mechanistic details in this footnote1). Initially, VAD leads to night blindness (difficulty seeing when there is low illumination) and also results in thickening of the skin epidermis (known formally as hyperkeratosis or phyrnoderma). If vitamin A supplementation is done at this stage, vision can be spared. However, prolonged VAD results in structural changes to the retina (the part of the eye that senses light and transmits those signals to the brain to be interpreted as visual input), which can cause a condition known as xerophthalmia (warning- images of diseased eyes in that link). In addition to its effects on the eyes and skin, vitamin A is a key regulator of normal immune responses. I reserve the cellular details of vitamin A function for the footnotes2. The specifics of the effect of vitamin A on the immune response is extensive, but as it relates to protection from infections, vitamin A is particularly important for a few specific aspects of immunity (these effects are dose-dependent):

Promotes homing of T cells to the gut by inducing expression of α 4β7 integrin and CCR9

Promotes differentiation of T cells into (induced) regulatory T cells and suppresses differentiation into Th17 cells to minimize tissue damage from inflammation in response to infectious threats

Promotes differentiation of T cells into effector T cells that clear infectious threats from the body

Promotes retention of T cells as tissue-resident memory T cells that do not recirculate through the body and are primed to rapidly respond to infection upon re-exposure

Promotes generation of IgA antibodies that defend mucosal surfaces without provoking inflammation, as well as IgG antibodies (though not as much as IgA)

Promotes differentiation of B cells into plasma cells which secrete massive quantities of antibody

Among many other functions. In a highly reductive sense, vitamin A’s principal immunological role appears to be the maintenance of barrier integrity, especially at the intestine. In the setting of vitamin A deficiency, deaths from infectious diseases are a major risk, and introduction of vitamin A supplementation in regions where there is a high prevalence of vitamin A deficiency has been shown to lower childhood mortality by 11 to 30%, mainly as a consequence of a decline in deaths from infectious diseases. With regard to measles specifically, meta-analyses encompassing over 1 million children find that vitamin A supplementation to children from 6 months to years of age reduces mortality by about 12%; when looking at children specifically under 2 years of age, 2 (age- and weight-appropriate) doses of vitamin A given 24 hours apart are able to lower mortality by 79%, though this is based overwhelmingly on data from countries where VAD is endemic. Note that vitamin A does not prevent acquisition of infectious diseases nearly as much as it promotes recovery from them. This means that vitamin A will not stop transmission of any infectious disease.

Importantly, vitamin A deficiency in the US is rare (0.3% in 2013). In higher income countries, the risk of toxicity from vitamin A supplementation is a much more salient concern, usually occurring through overconsumption of supplements or in some cases the livers of certain animals (polar bear liver is known for it). Toxicity from vitamin A manifests in any of 3 ways:

Acute toxicity- ingestion of megadoses of vitamin A over a short period of time produces nausea, vomiting, headache, dizziness, irritability, blurred vision, and muscular incoordination, and in more severe cases increased intracranial pressure and bone pain.

Chronic toxicity- occurs from prolonged consumption of doses above the tolerable upper intake (but not megadoses) over a prolonged period (weeks to months). Symptoms include dry, cracked skin, hair loss, brittle nails, fatigue, loss of appetite, bone and joint pain, and liver enlargement.

Teratogenicity- occurs from overconsumption of vitamin A during early pregnancy. Can result in spontaneous abortion, cardiac anomalies, and microcephaly, among other issues.

Because of the fat-soluble nature of vitamin A, overdose is very much possible as excess vitamin A is not simply lost in the urine as it is for water-soluble vitamins. Additionally, though vitamin A-rich diets have been associated with a reduced risk of cancer, there is some evidence that overconsumption may increase the risk of lung cancer. Excessive levels of vitamin A are also suggested to increase the risk of bone fracture and preclinical work shows that vitamin A promotes bone resorption. Young children are particularly prone to overdose.

The assessment of a person’s vitamin A status can be complicated by the fact that serum levels do not always accurately represent liver reserves, and multiple conditions can cause discordance between vitamin A status and serum levels (such as may occur with measles- more on that in a bit). The detailed mechanisms regulating release of vitamin A from hepatic stellate cells in response to the body’s physiological demands are not well understood.

Recommended daily allowances for vitamin A vary with age and sex and depend on the form of vitamin A:

Vitamin A in the diet can be obtained in an active form as retinol (or retinaldehyde or retinoic acid) from organ meats such as liver and eggs or in the form of inactive precursors such as β-carotene or β-cryptoxanthin, from vegetables and fruits (see above). Cooking the vegetables often helps to liberate vitamin A for absorption, as does consuming them with some fat. Vitamin A can also readily be obtained by infants from breastmilk in appropriate quantities provided that the source of the breastmilk has normal vitamin A levels. Because the activity of vitamin A differs depending on the form it takes, the recommended daily allowances for vitamin A are described in retinol activity equivalents (RAEs). 1 RAE is defined as 1 μg of retinol (0.003491 mmol), 12 μg of β-carotene, and 24 μg of other provitamin A carotenoids; the IU (international units) nomenclature is still seen but is outmoded. Under this system, 1 μg of retinol equal to 3.33 IU of retinol and 20 IU of β-carotene.

Because vitamin A is fat-soluble and effectively stored within hepatic stellate cells, deficiency generally does not set in immediately and instead requires prolonged deprivation from vitamin A, but it can occur with certain types of dietary patterns. For example, rice is a staple in many cultures, but is lacking in vitamin A. This led to the development of golden rice. Golden rice is modified to contain the machinery needed to make β-carotene, and this is transformed into active vitamin A once absorbed. Leafy green vegetables are a major source of vitamin A as well, but absorption is aided by cooking to help release the vitamin A from the plants.

Risk of vitamin A toxicity is greatest when consuming it in the form of active vitamin A (i.e. retinol) rather than retinyl esters or precursors like β-carotene.

A note on Supplement Use

Regulation of dietary supplements in the US is remarkably lax and the consequences of this are alarming. Studies consistently find that the contents of supplements do not match their labeling information, including both the presence of undisclosed ingredients and potentially dangerous adulterants such as heavy metals like cadmium and lead. With regard to vitamin A, one study found a majority of supplements (71%) for vitamin A did not contain quantities within 20% of what was indicated within the labeling information and values of vitamins within supplements ranged from undetectable levels to nearly double that which was indicated on the label. This means that it can be exceedingly difficult to ensure adequate intake of vitamin A (or other micronutrients) through reliance on supplements. Note that the margin between recommended daily allowance and upper limit for active forms of vitamin A (retinol, retinaldehyde, retinoic acid) can be quite narrow depending on the age group- it is very easy to get too much vitamin A or too little. Because of these complexities, vitamin A supplementation in the setting of measles (and in general) is best overseen by a qualified health professional.

Measles and Vitamin A

In the interest of not belaboring the point, I will refer interested readers to this post describing major misconceptions about measles and the role of vaccination in preventing it, but suffice it to say that a vaccine that has 97-99% effectiveness against measles for a period spanning decades if not life and is capable of eliminating the disease altogether as it has done in many countries around the world is vastly superior to vitamin A, which has no clear benefits for measles outcomes other than mortality and only clearly there in cases of existing vitamin A deficiency. It is also critical to bear in mind that much of what is most feared about measles is not the acute risk of death from the infection itself but the delayed consequences of the infection such as subacute sclerosing panencephalitis and post-measles immune amnesia.

Straw men being straw men, I will state this explicitly: the point of my comment here is not to suggest that diet is not an important aspect of human health and physiology and that maintaining adequate levels of micronutrients is not relevant- but with respect to protection from infectious diseases, nothing comes close to the power of vaccines, and this is especially evident in the case of measles. Still, there is perhaps an irony in the fact that people want to pin protection from infectious diseases on nutrition (instead of vaccination) in that infectious diseases themselves can cause malnutrition.

Measles has been reported to reduce vitamin A levels, and the severity of measured serum vitamin A deficiency during measles does correlate with disease severity- but the degree to which this relationship is causal has some complexity. Vitamin A levels in general drop in the serum in response to infection or inflammation -it is a negative acute phase reactant- and then normalize in the 7-28 days following infection; however, vitamin A levels within the liver do not appreciably change during these periods and vitamin A continues to be released from the liver at a constant rate. It has also been suggested that vitamin A levels may appear to drop because retinol in complex with its binding proteins is leaking out from the circulation as a consequence of the inflammatory response. Taken together, though the findings that low vitamin A levels correlate with measles severity are robust, there is a genuine question about the causality of this relationship as a more severe measles infection would be more likely to cause a greater decline in serum retinol levels, which may not necessarily reflect true retinol reserves3.

Nonetheless, measles can cause bona fide vitamin A deficiency through several mechanisms. The first of these is simply that during the period of acute illness, measles induces reduced intake of nutrients in general, with caloric intake being reported to drop as much as 75%. Furthermore, illness increases the metabolic demands on the body itself, leading to some consumption of vitamin A. In general, these are transient and will resolve over time, and the risk of true deficiency setting is dependent on prior reserves of vitamin A in the liver. Infection, including with measles, can also cause loss of vitamin A in the urine through a failure of proximal tubular reabsorption of retinol-binding protein 4. However, measles can provoke a considerably more serious form of malnutrition through infection of the intestines.

It has been reported that measles itself can provoke vitamin A deficiency by triggering a protein-losing enteropathy after the acute infection that inhibits effective absorption of vitamin A from the diet. In essence, this causes loss of nutrients from the interstitial fluid through leakage into the intestine owing to impaired integrity of both the intestinal epithelial barrier and intestinal lymphangiectasia. Children infected with measles early in life tend to have poorer growth and development than their uninfected counterparts. Because antibodies and lymphocytes are also lost in protein-losing enteropathy, this condition can render individuals more susceptible to infection, which may explain some of the beneficial effects observed on all-cause mortality from the introduction of measles vaccines.

Despite the strong recommendation from WHO and other expert bodies that vitamin A be offered in cases of severe measles, especially severe measles, the data on its benefit are much messier than Kennedy’s remarks suggest. The 2005 Cochrane review of vitamin A use in measles (which as far as I can tell is the most recent one on the question) found 2 doses of vitamin A 24 hours apart were essential for protection from measles mortality with a very large effect in children under 2- but no effect was seen with a single dose. However, the systematic review relies on studies conducted in areas where vitamin A deficiency is prevalent. Furthermore, though the systematic review was able to identify 8 relevant randomized controlled trials, the aggregate sample size of all participants in the studies was under 3000. This is not by any means disqualifying, but considerations regarding the sample size and populations are relevant in discussing the effect of vitamin A on measles outcomes, and in particular, some of the most feared outcomes of measles are relatively rare and would be hard to capture with statistical certainty in a sample of this size. Importantly, in a 2022 systematic review from Cochrane on vitamin A supplementation in general, the review found (emphasis mine):

There was no evidence of a difference for VAS on mortality due to measles (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.11; 6 studies, 1,088,261 children; low‐certainty evidence), respiratory disease (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.12; 9 studies, 1,098,538 children; low‐certainty evidence), and meningitis.

It’s also worth noting that in a study of hospitalized measles patients (albeit nonrandomized) in Italy (a higher income country where deficiency is rare), no effect was seen from vitamin A treatment on outcomes, but this study was relatively small.

This is not to argue that vitamin A should not be given in cases of measles. Age- and weight-appropriate doses are very low risk and may have significant benefit. However, vitamin A is far from the most important factor in protection from measles- vaccination status and population levels of immunity are. This has been made abundantly clear in recent tragic outbreaks, such as Samoa in 2019, where, despite the deployment of vitamin A as per WHO recommendations, 5700 people became infected with measles and 83 died, most of whom were children- and this is on top of the fact that Samoans generally do not have a high burden of vitamin A deficiency.

Nutrition is a key aspect of health and should never be neglected. It is thoroughly uncontroversial that our current food environment is not conducive to optimal health. But that doesn’t mean that we should disregard the value of other triumphs of science and medicine that have enormously improved the human condition.

Vitamin A is not a replacement for measles vaccination.

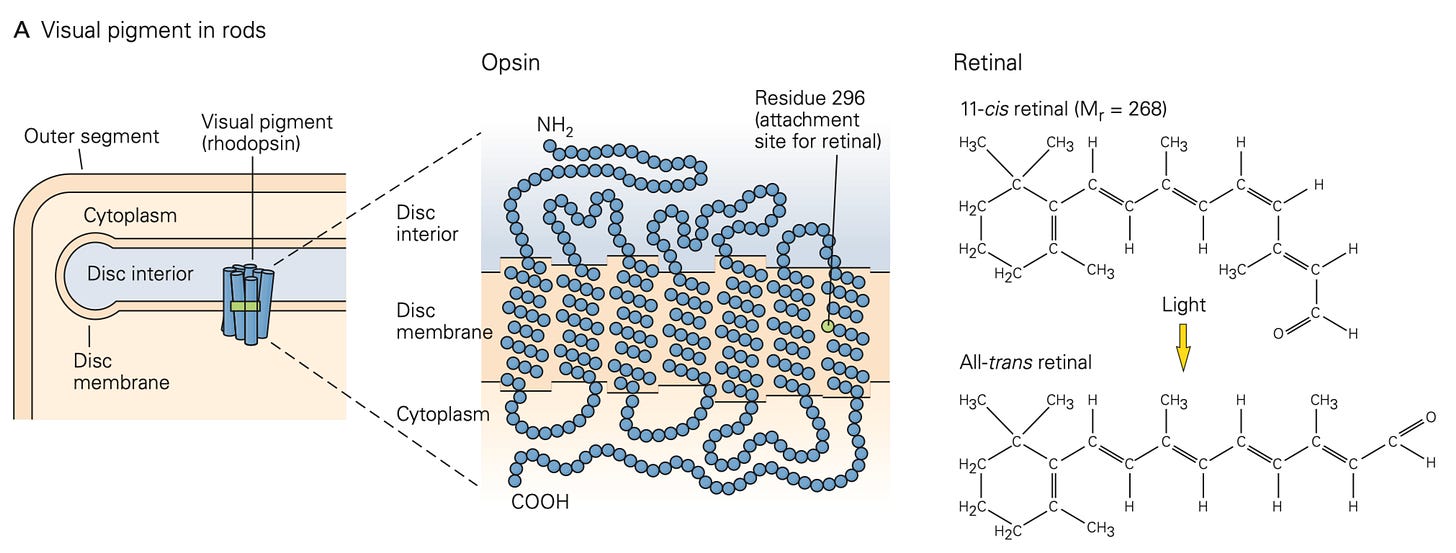

11-cis retinal (aka retinaldehyde) is covalently linked as an ε-amino group lysine (Schiff base) to a protein known as opsin found within the disc of photoreceptors.

When light (of the relevant frequency) reaches the photoreceptor, it undergoes an isomerization to become all-trans retinal.

This complex of rhodopsin with all-trans retinal (known as metarhodopsin) can diffuse through the disc membrane of the photoreceptor until it encounters transducin. Transducin normally binds GDP but interaction with metarhodopsin promotes exchange to GTP and release of the α-subunit with bound GTP occurs until this subunit complexes with disc membrane associated phosphodiesterase. The phosphodiesterase converts cGMP to GMP. cGMP is required to keep the cGMP-gated Na+ ion channel on the photoreceptor membrane open, and when lost, the channel closes, flux of Na+ into the photoreceptor stops, which causes the photoreceptor to hyperpolarize. This sends the signal to the retina and into the brain that light is present. In the darkness, the cGMP is continuously produced and the photoreceptor remains depolarized.

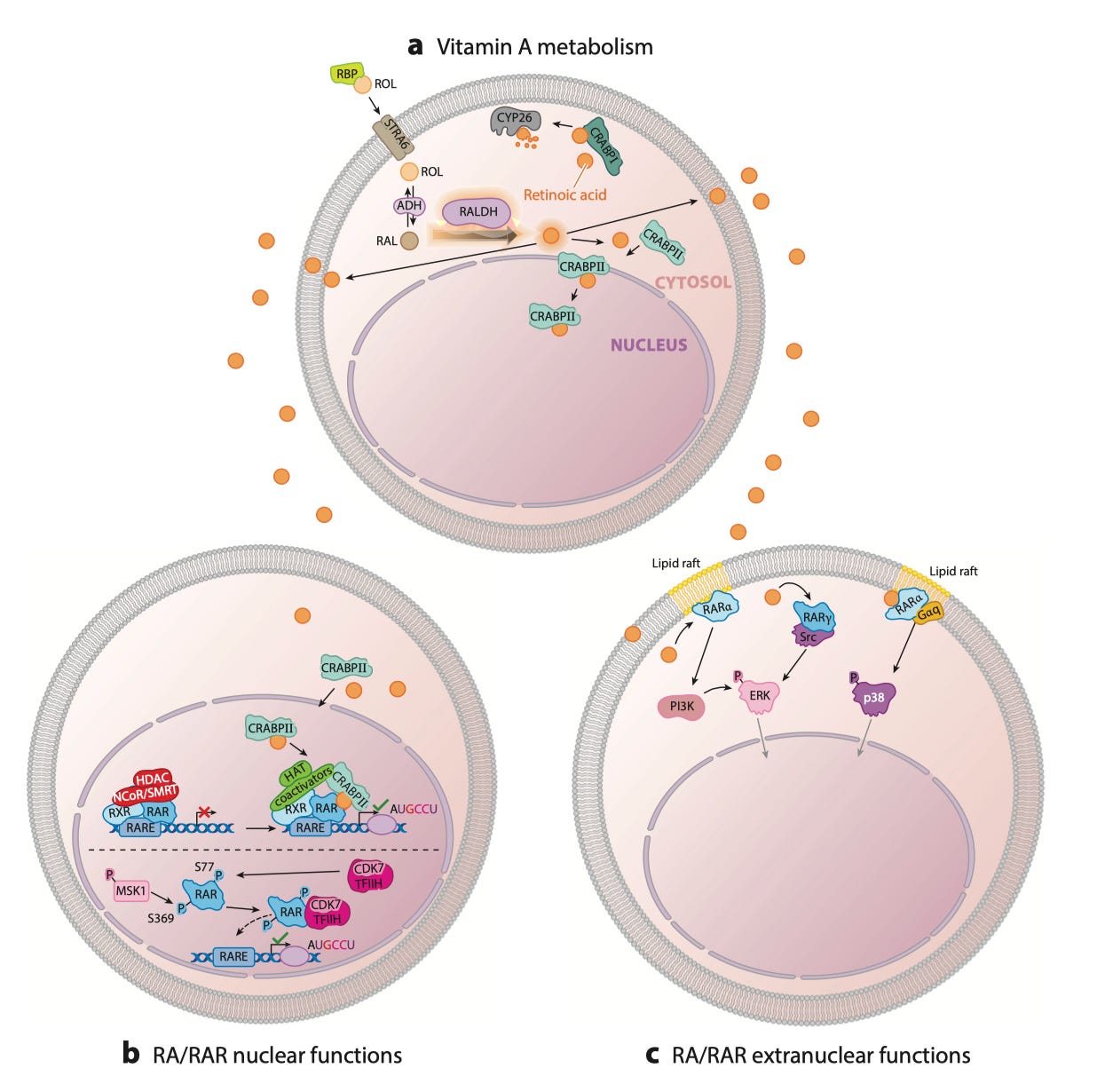

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin initially obtained from the diet most commonly in the form of precursors such as β-carotene or retinyl esters (usually linked to palmitate). Effective absorption requires it be present together with other lipids. Once at the brush border, intestinal epithelial cells package vitamin A into chylomicrons and can process these further into chylomicron remnants that are released into the circulation. Because vitamin A has to be co-packaged with lipids, diets very low in fat carry a significant risk of vitamin A deficiency.

The vitamin A is then stored in hepatic stellate cells (aka Ito cells) as retinyl esters. Vitamin A can be hydrolyzed into its active form within hepatic stellate cells (as retinol) which can be released in complex with retinol binding protein (RBP) and transthyretin (TTR). This trimolecular complex is important for preventing renal losses of vitamin A. RBP can be sensed by cells via the STRA6 receptor to facilitate entry of retinol into cells. Retinol is the major form of vitamin A found in the circulation. Inside the cell, retinol can bind to CRABPII to enter the nucleus and exert effects on gene transcription or can be targeted for degradation via CRABP1.

Once in the nucleus, vitamin A can bind to retinoic acid receptors (RARs) or retinoid X receptors (RXRs) to alter gene transcription and change cellular behavior. There are 3 subtypes of each receptor (RARα, - β , and - γ; RXRα, - β , and - γ) with multiple isoforms. RAR and RXR often exist as a heterodimer. RXRs frequently form heterodimers with vitamin D receptors (VDRs), thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and lipid X receptors (LXRs). In the absence of vitamin A, RARs are generally bound to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) in the DNA ligated to a co-repressor like SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor) and NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) to block their transcriptional effects. This is relieved by the addition of vitamin A.

Vitamin A also has non-genomic mechanisms of action that are essential for vision, as described in the previous footnote. Within the cytosol, unligated RARα is able to bind cytosolic RNAs to repress translation. If vitamin A in the cytosol interacts with RARα it can induce p38 MAPK signaling to alter cell proliferation. RARα is frequently associated with lipid rafts.

In general, the mechanisms by which vitamin A could contribute to an antiviral effect with measles is not well characterized. Some in vitro work suggests that vitamin A can enhance expression of RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) which can arrest replication of the measles virus through induction of the interferon response. At the same time, vitamin A promotes differentiation of T cells into regulatory cells that can help to dampen the toxicity of the immune response on surrounding tissues.