We may already have the first Alzheimer's Vaccines

But a lot more work needs to be done to tell us for sure.

Back in 2023, a preprint was posted looking at the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in a cohort of Welsh older adults based on their vaccination status. It found that receipt of the live attenuated shingles vaccine Zostavax was associated with a 3.5% lower absolute risk of developing dementia over the next 7 years, equivalent to a 19.9% relative reduction. Put another way, it looked like getting the shingles vaccine cut your chances of developing dementia by about a fifth, which is not huge, but far from nothing. This wasn’t the first study to suggest a protective effect of vaccination against shingles on the development of dementia, but these types of studies make it hard to make a claim that some exposure caused the outcome because they do not randomize the exposure. This means that there could always be factors we aren’t accounting for, despite the factors we do try to control for, that affect our results. This preprint, however, was unique because of one key feature: eligibility for vaccination was determined by a strict birthday cutoff. Everyone born after September 2, 1933 was eligible for the vaccine while those born earlier were never eligible. This creates a massive disparity in uptake of the vaccine among adults who are, generally speaking, of a similar age:

Comparison showed that the adults in both groups were generally very similar by other characteristics, which meant that this preprint showed the results of, essentially, a natural experiment. This is still not random, but it’s pretty close. Importantly, evidence of a clear protective effect was restricted to women:

which the authors attribute in part to the fact that shingles and dementia risk in general are higher in women (which motivated the sex-stratified comparison). However, the vaccine here, Zostavax, is no longer available in the US, in large part because it was far less effective than the recombinant shingles vaccine, Shingrix. The natural question that followed was: does Shingrix reduce your risk of dementia?

An attempt to answer that question was delivered to us in July 2024 by a very similar approach: rollout of Shingrix began later than Zostavax, and over time there was a dramatic shift in the share of vaccinated people getting Shingrix vs. getting Zostavax:

And in this case, we saw that receipt of the recombinant shingles vaccine was associated with a 17% increase in diagnosis-free time (164 additional days without a diagnosis of dementia in those who would develop it) compared with those receiving the Zostavax vaccine, with the effect again being stronger in women than men (22% versus 13% more time lived diagnosis-free):

Notably, as a check on the validity of the study design, the researchers looked to see how the effect compared with those of other routine vaccines, and Shingrix was clearly better at prolonging time without a dementia diagnosis.

While this work is compelling and suggestive, some would argue that we still need something more definitive. The definitive answer would require recruiting large groups of older adults and randomizing them to receive the shingles vaccine or a negative control, and following them for many years to see how the incidence of dementia between them compares. This, however, is unethical because it would mean withholding a safe and effective vaccine from a population very vulnerable to the disease the vaccine prevents (shingles causes among the most excruciating pains known to man, and if not treated promptly can cause a chronic pain condition because of scarring of the nerves). In situations where the gold-standard randomized controlled trial is not realistic or unethical, deciding both that a causal relationship is present and the direction of causality can be aided with a well-defined mechanism for how the exposure produces the response. For the most part, we haven’t really had that with the evidence so far. There’s a bunch of literature suggesting that herpesviruses like varicella zoster virus (VZV, the cause of chickenpox and shingles) has some role in the development of dementia, but what that role is is not clear.

Now, hot off the presses, we have a study that seems to fill in that gap:

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are a risk factor for Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) and are thought to be the major drivers in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Autopsies on those who experienced TBIs long after those injuries first occurred show key pathologic findings that are found with Alzheimer’s disease (neurofibrillary tangles, β-amyloid plaques). One of the hypotheses for the causation of AD is that it is driven by herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), the same virus that causes cold sores, invading the brain as a consequence of the immune system’s natural decline with age, causing the pathologic changes of AD through reactivation, with a possible additional role for other herpesviruses, including VZV. Interestingly, the strongest genetic risk factor for the development of AD, ApoE4, is also associated with a heightened risk of herpes labialis (cold sores). Furthermore, some data suggests that brain injury can trigger herpesvirus reactivation, and further that this is associated with a worse prognosis. To see if HSV-1 could explain the link between AD and TBIs, the team used 3D human brain tissue cultures and reproduced different types of TBIs. The study itself is thorough and interesting, but in the interest of keeping the post focused, I will limit discussion to its key relevant finding:

Closed head injury (CHI) of the culture cells resulted in the reactivation of HSV-1 in infected neurons and pathologic changes associated with AD were seen essentially entirely in the neurons infected with HSV-1 and not in control neurons that also underwent CHI. This, coupled with the epidemiological evidence on TBIs and dementia, offers compelling support for the idea that HSV-1 is at least one of the drivers of AD in those with a history of TBIs.

The natural question here, however, is how shingles might fit into this picture. For that, we need to go to another study. Again, in the interest of concision, here’s the relevant piece:

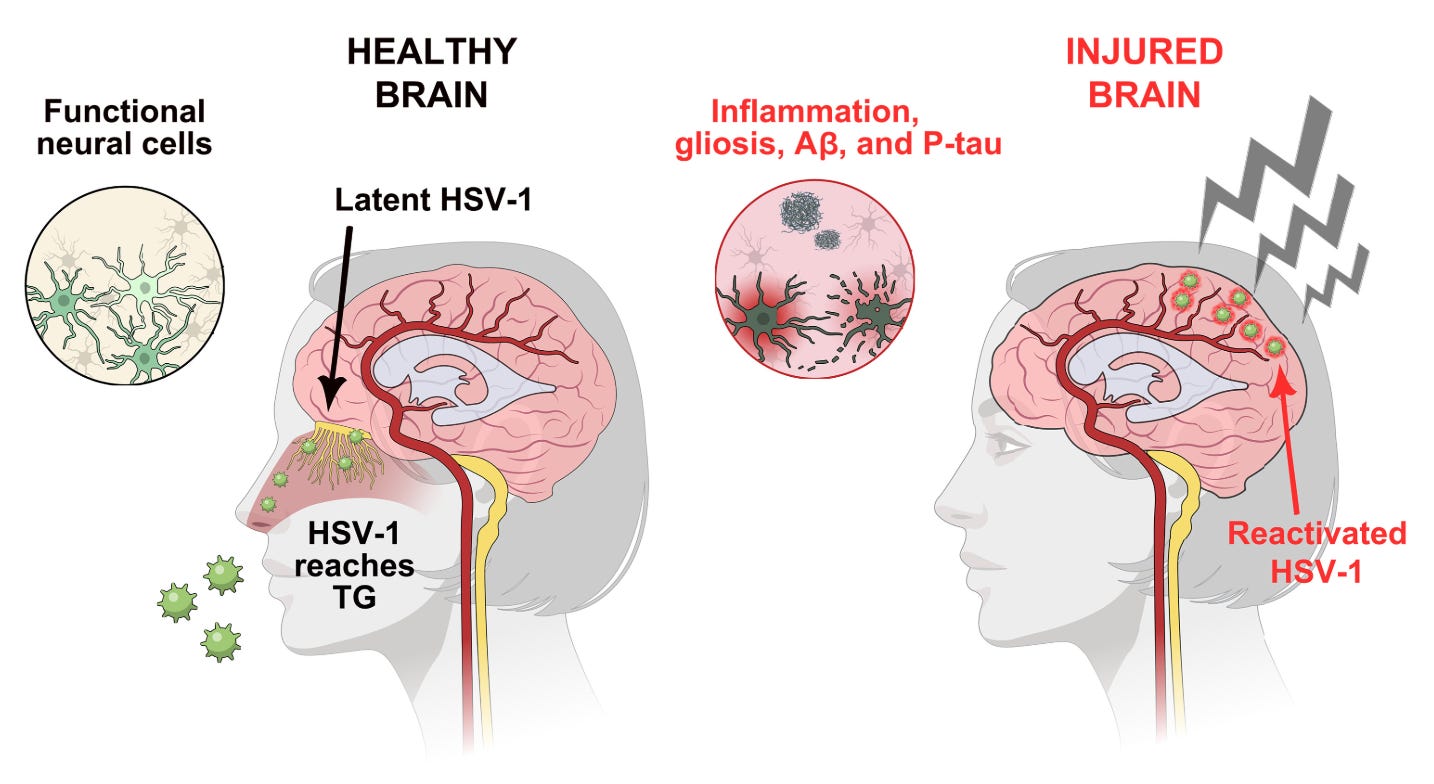

Neural stem cells infected with HSV-1 do produce β-amyloid plaques, but the virus can be suppressed with an antiviral medication (in this case, valacyclovir, VCV). If however you throw varicella zoster virus into the mix, even VCV cannot suppress HSV-1 in this model, and reactivation occurs, with attendant β-amyloid (Aβ) plaque appearance. This gives rise to a model for the development of dementia shown below from Cairns and colleagues:

Initially, HSV-1 infects the brain, presumably through the trigeminal ganglia. Once there, it reactivates in response to injury, wherein it triggers the pathologic changes seen in AD. Adding in the tissue culture and epidemiological evidence we have, this suggests that VZV can trigger reactivation of HSV-1 within the brain, aggravating the risk of dementia. Vaccination against VZV, therefore, offers a clear path to interrupt this sequence of events by making it less likely that HSV-1 will reactivate, and thus less likely that the neurological changes associated with AD will develop.

Now, like many mechanisms, this is all very seductive, but it remains to be proved. There could be alternative explanations for these epidemiological findings, and while the tissue culture work is rigorous, it does not recapitulate the complexity of an actual person. This work also does not suggest that HSV-1 is the only causal factor in the development of AD- there may be other ones which preventing HSV-1 reactivation would not address. At the end of the day though, VZV alone is a terrible virus that is known to cause terrible disease, and that alone justifies widespread vaccination against it. However, this evidence also suggests that safe and effective HSV-1 vaccines may be particularly valuable in preventing AD. If we can get such vaccines, that could offer a definitive answer regarding a role of HSV-1 in AD. In addition to these, studies looking at treatment of AD with antiherpesvirals are currently in progress, and could lend further credence to the role of these viruses in AD (or rebut it).

These results are particularly interesting given that we routinely vaccinate children against varicella (chickenpox)- perhaps they will already have a lower risk of dementia because of this alone. However, because these vaccines were introduced in 1988 in Japan and Korea, we probably don’t have anyone in this group old enough to have developed AD, unless we consider devastating, very early onset familial forms of the disease, but even in these individuals, the cases would only just now start to become apparent. We’ll have to be patient- but in the interim, it’s exciting to think that we may already have several effective means to reduce the likelihood of contracting Alzheimer’s disease.